A Very Special Place in Otto History:

The Confluence of Coweeta Creek

and The Little Tennessee River in Otto, North Carolina

The earliest studies place both villages and settlements in and around Otto as early as 1000 BCE. Very few studies are available regarding this period. One such study is the following authored in 1992 by Jennifer Martin of Asheville, NC - under contract with the United States Department of the Interior - National Park Service National Register of Historic Places:

Study Title:

Historic and Architectural Resources of Macon County, North Carolina, ca. AD 600-1945

One great source of historical information lies here: Website: Tessentee Bottomlands Preserve

Western North Carolina Cherokee Villages

This map shows some early Cherokee Towns and Trails in Yellow

In the footsteps of the explorers

There are several prominent names that have contributed greatly to the study of Otto History and Archaeology. Here is a brief history of these current and past archaeological and cultural pioneers.

|

Joffre Coe operating a bulldozer in 1966 at the Coweeta Creek site. Coe was the dominant figure in North Carolina archaeology for almost 50 years. Image via courtesy of the Research Laboratories of Archaeology.

The first book on the history and prehistory of North Carolina's Indians was published in 1947 by the Reverend Douglas Rights, with two chapters devoted to archaeology and antiquities. Rights, an avid artifact collector was first president of the Archaeological Society of North Carolina when the group was organized in 1933. But it was a young teenager at that meeting, Joffre Lanning Coe, who soon led North Carolina into the era of scientific archaeology. In the 1930s, Coe, who was in close contact with the University of Chicago's prominent archaeology program, lay out a strategy for surveying the state. From then until his retirement from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 1982, the enthusiastic Coe dominated the state's archaeological endeavors.

|

This book written by Ora Blackmun; Western North Carolina: Its Mountains and Its People to 1880 - published in 1977 - contributed greatly to the cultural and knowledge base.

This book written by Ora Blackmun; Western North Carolina: Its Mountains and Its People to 1880 - published in 1977 - contributed greatly to the cultural and knowledge base.Other academic works on Otto History expand further on Cherokee History. The following reference covers one of those studies. It was published in The Journal of Southeastern Archaeology in the Summer of 2002 and edited by Christopher B. Rodning and Amber M. VanDerwarker. Dr. Rodning, a professor at Tulane University, is considered to be one of the foremost authorities on Western North Carolina Antiquity.

REVISITING COWEETA CREEK:

RECONSTRUCTING ANCIENT CHEROKEE LIFEWAYS IN SOUTHWESTERN NORTH CAROLINA

During the 1960s and 1970s, archaeologists affiliated with the Research Laboratories of Anthropology (RLA) at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) conducted fieldwork at the Coweeta Creek site (31MA34) and other sites in southwestern North Carolina as part of a regional study of the origins and development of Cherokee culture.

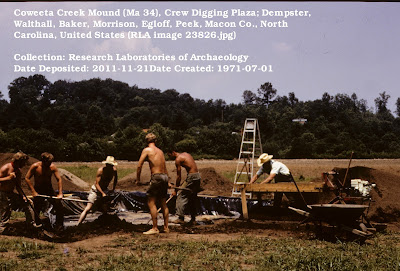

Locations of the Explorations: Coweeta Mound Site 31MA34

Photo is of the project team from July 1971

The Coweeta Creek site, a mound and associated village in the upper Little Tennessee Valley, was excavated from 1965 to 1971 by the Research Laboratories of Anthropology (RLA) at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill as part of the Cherokee Archaeological Project.

The primary goal of this broader regional project by the RLA was to reconstruct the origins and development of Cherokee culture in the Appalachian Summit province of Western North Carolina. Case studies included in this collection concentrate on select aspects of the archaeological record from Coweeta Creek to explore native lifeways at this ancient Cherokee town.

Here is a Clay Pipe recovered virtually intact from the Coweeta Mound Site:

The Coweeta Creek site includes a townhouse mound and village that dates to the protohistoric and perhaps the late prehistoric periods, although pinpointing the beginning and ending points of its long and complicated settlement history still demands further consideration. There was no recognized Middle Cherokee town at Coweeta Creek in the mid-and late eighteenth century when European colonists began describing and map- ping this cultural landscape, but European trade goods are associated with late stages of the mound. The articles collected here exemplify recent interest in the archaeological record at the Coweeta Creek site.

Why is Otto so Dominant in Western North Carolina History?

At present the most abundant source of evidence about native lifeways from the sixteenth through the early eighteenth centuries is the Coweeta Creek site, located north of the confluence of Coweeta Creek and the Little Tennessee River. One outcome of UNC's Cherokee Archaeological Project has been an archaeological framework for culture history in western North Carolina. Cultural historical phases from the Early Archaic through Early Historic periods have been outlined.

Middle Qualla vessels from the Coweeta Creek site. The bottom two vessels are cazuela bowls with incised designs between the rim and shoulder; the top two vessels are jars with incised, punctated, and applied-clay decorations.

Much of the material culture recovered at Coweeta Creek is attributable to the Qualla phase, which spans the late fifteenth through early nineteenth centuries in southwestern North Carolina . Surface treatments and rim modes of Qualla pottery resemble those of Mississippi period Pisgah-series pottery in western North Carolina, and those of the sixteenth-century Túgalo and eighteenth-century Estatoe series of northeastern Georgia and northwestern South Carolina. Ceramics from the Coweeta site are clearly attributable to historic Cherokee settlements in Western North Carolina.

Two views of the Coweeta Creek mound during excavation: view with the plowzone, sand floor and daub fall removed, revealing Structure 1 (top, looking northeast); and Floor 3 of Structure Group 1 (bottom, looking northwest). (Courtesy of the Research Laboratories of Archaeology).

Visual impressions of site boundaries and artifact concentrations were noted on maps drawn in the field. The large quantity of potsherds recovered from Coweeta Creek led to controlled surface collections, and to the excavation of several test pits that yielded considerable amounts of pottery. Most of the artifacts found on the ground surface at Coweeta Creek came from the mound, although several concentrations, which correspond roughly to the locations of domestic houses at the site, were present in the village.

The Coweeta mound comprises several stages of a public architectural form known as a townhouse. Positive results from surveys and test excavations at Coweeta Creek led to its selection for more extensive excavation comparable to the ongoing investigations at other sites in western North Carolina, such as Garden Creek and Warren Wilson. Hundreds of artifacts were present on the ground surface at Coweeta Creek, and further study promised to yield valuable results. Surface collecting at Coweeta Creek recovered significantly more artifacts than were found at many other sites in the upper Little Tennessee Valley inspected by RLA archaeologists during the Cherokee Archaeological Project. The Otto farmer and landowner offered access to the field along the Little Tennessee River, near the contemporary town of Otto where the Coweeta Creek site is located. Contiguous excavations commenced in June 1965, and fieldwork continued at Coweeta Creek until August 1971, during long field seasons that ran from the late spring through the fall each year.

Excavations of the Coweeta Creek mound continued from 1965 to 1969. The mound, which stood some 4 ft. tall prior to excavation, represents the remnants of at least six stages of a public structure, the townhouse, with each manifestation built directly atop the dismantled and burned remnants of its predecessor. At most, several inches separated the packed floors of successive stages of this large structure.

It was immediately apparent that remnants of earlier manifestations of this structure were present lower down in the mound, and that excavating the mound would be more complicated than originally thought.

Much of the material recovered from the thin lenses of fill between floors was architectural rubble, including burned daub, charred wood, and burned sand and clay. Considerable numbers of potsherds and other artifacts, as well as archaeobotanical and zooarchaeological specimens, found their way into the floor debris deposits and into the lenses of fill between floors. Most of the articles in this thematic collection draw comparisons between material culture derived from different deposits at Coweeta Creek, particularly from the townhouse.

Undoubtedly some of the material found in townhouse floor deposits directly related to the "life" of each stage of this public structure. But it is also likely that much of this material was dumped onto the dismantled and burned remnants of "dead" townhouses, perhaps for symbolic reasons as well as for the practical purpose of creating a surface for a new townhouse.

Nevertheless, the debris itself conceivably had multiple origins, including feasts that were part of townhouse renewal events and the disposal of debris from activities that occurred in the plaza and in domestic areas of the site. The deposits lying on the floors of different stages of the Coweeta Creek townhouse may have different origins. This is especially important to consider if indeed the last stages of the townhouse were buried and rebuilt after the village was largely, if not wholly, abandoned.

It seems most likely that the patterns of dismantling, covering, and rebuilding the townhouse were relatively similar for all stages of the mound, which itself is an outcome of a series of structural episodes, rather than a mound built specifically as a substructural platform.

Given the minimal thickness of fill episodes between successive floors, hundreds of postholes from later stages of the Coweeta Creek townhouse probably intruded into earlier levels of the mound and cut through one or more floors.

Potsherds may have been intentionally placed in postholes as shims and others undoubtedly migrated downward as postholes filled. Similarly the rebuilding of the hearth, which was kept at the same spot in each stage of the townhouse, created intrusive features. For all these reasons, making clear cut analytical distinctions between materials found lying on floors or between floors of the Coweeta Creek townhouse is very difficult.

When excavation of the series of townhouses was completed, site investigations moved into areas surrounding the mound. At the eastern edge of the mound were remnants of covered ramadas that stood beside each manifestation of the townhouse. Layers of clay and clusters of river boulders in this part of the mound may be remnants of a ramp that sloped gently downward from the doorway of the townhouse to the plaza. Beneath the plow zone in the plaza were lenses of sand and clay, remnants of landscaping in this area of town.

European-made glass beads and kaolin pipe fragments were found in sand lenses in the plaza, as well as in overlying plow zone contexts. These lenses of sand and the artifacts within them most likely represent deposits from some of the latest events and activities that took place in the plaza, which was probably swept and otherwise maintained as a clean level surface as long as it remained in use by the community.

Excavation of the plaza and village area at Coweeta Creek occurred from 1969 to 1971. Isolated squares were dug north and northeast of the main excavation area in search of any signs of a stockade and to evaluate how much area might have been part of this settlement. Posthole patterns or other direct archaeological evidence of a log stockade have not been identified at the site. The compact arrangement of structures nevertheless suggests that a stockade surrounded the town. Several dwellings were uncovered in the village area. Surface collections covering some 3 acres suggest that many more were likely present south and east of the excavations. The village may have covered much of the bottomland between the excavated areas and the river, which runs some 300 ft. east of the mound. The scale of contiguous excavations at Coweeta Creek makes it one of the most extensively investigated native settlements in western North Carolina.

European trade goods present in late stages of the Coweeta Creek mound and plaza include glass beads, kaolin pipe fragments, and some metal artifacts. These indicate that the last stages of the townhouse at Coweeta Creek were built during the late seventeenth or early eighteenth centuries. The style and spatial patterning of public and domestic architecture at Coweeta Creek suggest that a formally planned town was founded in the late sixteenth century or perhaps even earlier. Structures at Coweeta Creek are similar to late prehis- toric houses found at Mississippian towns and villages in western North Carolina and in the upper Tennessee Valley

There are, however, significant differences between the architecture and settlement plan of Coweeta Creek and those of historic Cherokee towns in the southern Appalachians.

Paired summer ramadas and winter lodges are characteristic of Cherokee domestic architecture dating to the eighteenth century. At Coweeta Creek, postholes in the area between the plaza and village may represent lightly built ramadas comparable to historic Cherokee summer houses, but these ramadas are not specifically paired with other structures. The townhouse and domestic houses at Coweeta Creek more closely resemble Mississippian structures in their design than eighteenth-century Cherokee architecture. Houses at Coweeta Creek are comparable to those at late prehistoric sites such as Warren Wilson and Ledford Island.

Layout of the Coweeta Creek village also resembles Mississippian settlement plans more than the dispersed town plans characteristic of the eighteenth century. Clearly, the presence of European trade goods reflects the presence of some kind of settlement at Coweeta Creek at the dawn of the eighteenth century. By then, Coweeta Creek was probably very different from the nucleated town that existed at this locality in earlier centuries. Further assessment of the chronology and evolution of the settlement plan at Coweeta Creek is needed. Nevertheless, we know that its architecture and artifacts hold valuable clues about culture and community in southwestern North Carolina during the late prehistoric and early historic periods.

Many more adult men than women are present in graves within the Coweeta Creek townhouse, including one male elder with an engraved rattlesnake shell gorget and another with a quiver of seven arrows and a variety of other symbolically charged mortuary goods. The oldest women found in graves at Coweeta Creek were buried preferentially in and beside houses in the village, including one woman with a ground stone celt and two women with turtle shell rattles.

Dr. Rodning at Tulane has interpreted these spatial patterns to reflect the privileged access of women and men in this community to different kinds of power, primarily through men's involvement in the practice of diplomacy and war between towns and women's roles as leaders of matrilineal clans and households within towns. This interpretation situates these complementary forms of power in events and activities that took place primarily within the settings of public and household architecture, respectively.

Of course these data are critical for reconstructing subsistence practices of the community at Coweeta Creek. But social and ritual dimensions of foodways are also accessible through study of the Coweeta Creek collections. For example, the presence in the townhouse of bear bones and charred seeds from Ilex vomitoria, the leaves of which were brewed into the tea known as Black Drink, may reflect public ritual practices. Relative frequencies of maize cupules and kernels in different parts of the site offer clues about the organization of food processing tasks, and the study of vessel assemblages and grinding tools found at the site can add to our understanding of what, how, and where foods were prepared and eaten. Studies of gender and foodways have been identified as profitable directions for archaeologists interested in areas such as southern Appalachia (Claassen 1997, 2001a, 2001b). This collection of case studies is shaped in part by our own interests in these topics. Success in revisiting Coweeta Creek with these and other themes in mind raises prospects for revisiting other excavated sites in western North Carolina through collections-based research.

More work to be done:

Reviews of Cherokee archaeology in different areas of southern Appalachia have outlined several specific problems in studying archaeological cultures representing historic Cherokee peoples and their precontact ancestors. Archaeology at Coweeta Creek has much to contribute to dialogues and debates in this literature. What did Cherokee communities look like before nucleated town plans unraveled and were replaced by dispersed settlements characteristic of the late eighteenth century? How did social relationships within and between seventeenth-century towns and villages compare with eighteenth-century social dynamics and geopolitics? What was the nature of trade and exchange in southwestern North Carolina before and after the arrival of Europeans to the Southeast? How did the social composition of Mississippian and historic native households and communities in southwestern North Carolina compare to those in other parts of the Southeast? What kinds of activities took place in and around protohistoric Cherokee dwellings and townhouses, such as those at Coweeta Creek? What impacts would life in native towns such as Coweeta Creek have had on the woodland environments of southern Appalachia? Archaeological materials from Coweeta Creek represent significant data sets relevant to these and many other queries. The following set of Coweeta Creek case studies hopefully will spark further interest in this remarkably rich Cherokee site. These articles are neither a formal site report nor a thorough list of what materials are present in collections from Coweeta Creek. Nevertheless they do contribute to a foundation for the continued study of native lifeways in late prehistoric and protohistoric southwestern North Carolina

The articles in this collection specifically address the Coweeta Creek mound, which represents the ruins of several stages of a public structure. Rodning relates the architectural history of this townhouse to the nature of public life in the ancient town at Coweeta Creek. VanDerwarker and Detwiler compare and contrast the kinds and quantities of plant remains found on floors of the Coweeta Creek townhouse to those found in pits in both mound and village areas. They demonstrate a difference in disposal patterns between pit features in the village and near the townhouse, in addition to considering gendered patterns of food processing in public space. Wilson and Rodning identify the range of ceramic vessels made and used by people at the Coweeta Creek settlement. They offer a functional analysis of pottery assemblages as a baseline for future studies of Qualla phase pottery in the region. Lambert compares bioarchaeological indicators of health and life activity patterns at Coweeta Creek to those at two late prehistoric sites in western North Carolina, Warren Wilson, and Garden Creek.

The best source for this article came from Dr. Rodning on this website:

http://www.tulane.edu/~crodning/rodning2011A.pdf

Next Early History Article: The Pottery of the Eastern Cherokee

Much of the material culture recovered at Coweeta Creek is attributable to the Qualla phase, which spans the late fifteenth through early nineteenth centuries in southwestern North Carolina . Surface treatments and rim modes of Qualla pottery resemble those of Mississippi period Pisgah-series pottery in western North Carolina, and those of the sixteenth-century Túgalo and eighteenth-century Estatoe series of northeastern Georgia and northwestern South Carolina. Ceramics from the Coweeta site are clearly attributable to historic Cherokee settlements in Western North Carolina.

Two views of the Coweeta Creek mound during excavation: view with the plowzone, sand floor and daub fall removed, revealing Structure 1 (top, looking northeast); and Floor 3 of Structure Group 1 (bottom, looking northwest). (Courtesy of the Research Laboratories of Archaeology).

Visual impressions of site boundaries and artifact concentrations were noted on maps drawn in the field. The large quantity of potsherds recovered from Coweeta Creek led to controlled surface collections, and to the excavation of several test pits that yielded considerable amounts of pottery. Most of the artifacts found on the ground surface at Coweeta Creek came from the mound, although several concentrations, which correspond roughly to the locations of domestic houses at the site, were present in the village.

Some Truly Historic Otto Dwellings

|

| Cherokee Townhouse circa 1600 |

Excavations of the Coweeta Creek mound continued from 1965 to 1969. The mound, which stood some 4 ft. tall prior to excavation, represents the remnants of at least six stages of a public structure, the townhouse, with each manifestation built directly atop the dismantled and burned remnants of its predecessor. At most, several inches separated the packed floors of successive stages of this large structure.

It was immediately apparent that remnants of earlier manifestations of this structure were present lower down in the mound, and that excavating the mound would be more complicated than originally thought.

Much of the material recovered from the thin lenses of fill between floors was architectural rubble, including burned daub, charred wood, and burned sand and clay. Considerable numbers of potsherds and other artifacts, as well as archaeobotanical and zooarchaeological specimens, found their way into the floor debris deposits and into the lenses of fill between floors. Most of the articles in this thematic collection draw comparisons between material culture derived from different deposits at Coweeta Creek, particularly from the townhouse.

Undoubtedly some of the material found in townhouse floor deposits directly related to the "life" of each stage of this public structure. But it is also likely that much of this material was dumped onto the dismantled and burned remnants of "dead" townhouses, perhaps for symbolic reasons as well as for the practical purpose of creating a surface for a new townhouse.

Nevertheless, the debris itself conceivably had multiple origins, including feasts that were part of townhouse renewal events and the disposal of debris from activities that occurred in the plaza and in domestic areas of the site. The deposits lying on the floors of different stages of the Coweeta Creek townhouse may have different origins. This is especially important to consider if indeed the last stages of the townhouse were buried and rebuilt after the village was largely, if not wholly, abandoned.

It seems most likely that the patterns of dismantling, covering, and rebuilding the townhouse were relatively similar for all stages of the mound, which itself is an outcome of a series of structural episodes, rather than a mound built specifically as a substructural platform.

Given the minimal thickness of fill episodes between successive floors, hundreds of postholes from later stages of the Coweeta Creek townhouse probably intruded into earlier levels of the mound and cut through one or more floors.

Potsherds may have been intentionally placed in postholes as shims and others undoubtedly migrated downward as postholes filled. Similarly the rebuilding of the hearth, which was kept at the same spot in each stage of the townhouse, created intrusive features. For all these reasons, making clear cut analytical distinctions between materials found lying on floors or between floors of the Coweeta Creek townhouse is very difficult.

When excavation of the series of townhouses was completed, site investigations moved into areas surrounding the mound. At the eastern edge of the mound were remnants of covered ramadas that stood beside each manifestation of the townhouse. Layers of clay and clusters of river boulders in this part of the mound may be remnants of a ramp that sloped gently downward from the doorway of the townhouse to the plaza. Beneath the plow zone in the plaza were lenses of sand and clay, remnants of landscaping in this area of town.

Trade with the Visitors

European-made glass beads and kaolin pipe fragments were found in sand lenses in the plaza, as well as in overlying plow zone contexts. These lenses of sand and the artifacts within them most likely represent deposits from some of the latest events and activities that took place in the plaza, which was probably swept and otherwise maintained as a clean level surface as long as it remained in use by the community.

A Stockade Fence?

Excavation of the plaza and village area at Coweeta Creek occurred from 1969 to 1971. Isolated squares were dug north and northeast of the main excavation area in search of any signs of a stockade and to evaluate how much area might have been part of this settlement. Posthole patterns or other direct archaeological evidence of a log stockade have not been identified at the site. The compact arrangement of structures nevertheless suggests that a stockade surrounded the town. Several dwellings were uncovered in the village area. Surface collections covering some 3 acres suggest that many more were likely present south and east of the excavations. The village may have covered much of the bottomland between the excavated areas and the river, which runs some 300 ft. east of the mound. The scale of contiguous excavations at Coweeta Creek makes it one of the most extensively investigated native settlements in western North Carolina.

The Coweeta Mound - A Goldmine of Information & History

Artifact collections from Coweeta Creek represent an abundant source of data about native lifeways in late prehistoric and protohistoric southwestern North Carolina. The specimen catalog from Coweeta Creek lists over 600,000 artifacts, including more than 500,000 potsherds and more than 10,000 lithic artifacts. European trade goods present in late stages of the Coweeta Creek mound and plaza include glass beads, kaolin pipe fragments, and some metal artifacts. These indicate that the last stages of the townhouse at Coweeta Creek were built during the late seventeenth or early eighteenth centuries. The style and spatial patterning of public and domestic architecture at Coweeta Creek suggest that a formally planned town was founded in the late sixteenth century or perhaps even earlier. Structures at Coweeta Creek are similar to late prehis- toric houses found at Mississippian towns and villages in western North Carolina and in the upper Tennessee Valley

There are, however, significant differences between the architecture and settlement plan of Coweeta Creek and those of historic Cherokee towns in the southern Appalachians.

Coweeta shows real evidence of Mississippian Culture

Paired summer ramadas and winter lodges are characteristic of Cherokee domestic architecture dating to the eighteenth century. At Coweeta Creek, postholes in the area between the plaza and village may represent lightly built ramadas comparable to historic Cherokee summer houses, but these ramadas are not specifically paired with other structures. The townhouse and domestic houses at Coweeta Creek more closely resemble Mississippian structures in their design than eighteenth-century Cherokee architecture. Houses at Coweeta Creek are comparable to those at late prehistoric sites such as Warren Wilson and Ledford Island.

Layout of the Coweeta Creek village also resembles Mississippian settlement plans more than the dispersed town plans characteristic of the eighteenth century. Clearly, the presence of European trade goods reflects the presence of some kind of settlement at Coweeta Creek at the dawn of the eighteenth century. By then, Coweeta Creek was probably very different from the nucleated town that existed at this locality in earlier centuries. Further assessment of the chronology and evolution of the settlement plan at Coweeta Creek is needed. Nevertheless, we know that its architecture and artifacts hold valuable clues about culture and community in southwestern North Carolina during the late prehistoric and early historic periods.

The Footsteps of the First Otto Residents

Between 1965 and 1971, human remains representing 87 individuals from the Coweeta Creek site (31MA34), Macon County, NC were recovered during excavations conducted by the UNC-Chapel Hill archeologists. No known individuals were identified.

Note on Remains at the Coweeta Creek Mound:

The 391 associated funerary objects include shell ornaments, shell and glass beads, stone and clay pipes, stone disks and celts, objects of worked animal bone, and a clay pot.

The 391 associated funerary objects include shell ornaments, shell and glass beads, stone and clay pipes, stone disks and celts, objects of worked animal bone, and a clay pot.

Based on the collected remains, as well as the archaeological context and funerary objects, these individuals have been identified as Native American. Artifacts recovered at the Coweeta Creek site have been attributed to the Qualla phase which has been identified with both the protohistoric and historic Cherokee in western North Carolina.

More Work to be Done - More Otto History to be Uncovered

Recent Interests in the Coweeta Creek Site Collections from the Coweeta Creek site lend themselves to the study of many different aspects of native lifeways during these periods of Cherokee history. The original themes that motivated RLA fieldwork in western North Carolina in the 1960s and 1970s are still topics of considerable interest to contemporary archaeologists and ethnohistorians. Indeed, the relationship between historic Cherokee communities and ancestral groups represented by late prehistoric archaeological complexes remains an unresolved problem. The authors of the following articles have examined RLA collections from Coweeta Creek with interests in other anthropological issues, including themes different from those that guided fieldwork and interpretation by members of the Cherokee Archaeological Project.

Otto History - The Gender Gap Mystery

One thread in recent interpretations of archaeology at Coweeta Creek has been the relationship between gender and leadership in southern Appalachia during the late prehistoric and historic periods.Many more adult men than women are present in graves within the Coweeta Creek townhouse, including one male elder with an engraved rattlesnake shell gorget and another with a quiver of seven arrows and a variety of other symbolically charged mortuary goods. The oldest women found in graves at Coweeta Creek were buried preferentially in and beside houses in the village, including one woman with a ground stone celt and two women with turtle shell rattles.

Dr. Rodning at Tulane has interpreted these spatial patterns to reflect the privileged access of women and men in this community to different kinds of power, primarily through men's involvement in the practice of diplomacy and war between towns and women's roles as leaders of matrilineal clans and households within towns. This interpretation situates these complementary forms of power in events and activities that took place primarily within the settings of public and household architecture, respectively.

The Cherokee Diet

Another theme in recent archaeological considerations of Coweeta Creek is the study of ancient Cherokee food ways. Archaeobotanical specimens reflect the reliance of this community on cultigens such as maize, beans, and squash, as well as foraged resources such as nuts, fruits, and wild grasses. Peach pits found in the Coweeta Creek townhouse mound reflect adoption of Old World foods introduced to the Southeast by Europeans. Bones of deer, bear, and turkey are abundant; there is no evidence that residents of Coweeta Creek kept domesticated livestock. Of course these data are critical for reconstructing subsistence practices of the community at Coweeta Creek. But social and ritual dimensions of foodways are also accessible through study of the Coweeta Creek collections. For example, the presence in the townhouse of bear bones and charred seeds from Ilex vomitoria, the leaves of which were brewed into the tea known as Black Drink, may reflect public ritual practices. Relative frequencies of maize cupules and kernels in different parts of the site offer clues about the organization of food processing tasks, and the study of vessel assemblages and grinding tools found at the site can add to our understanding of what, how, and where foods were prepared and eaten. Studies of gender and foodways have been identified as profitable directions for archaeologists interested in areas such as southern Appalachia (Claassen 1997, 2001a, 2001b). This collection of case studies is shaped in part by our own interests in these topics. Success in revisiting Coweeta Creek with these and other themes in mind raises prospects for revisiting other excavated sites in western North Carolina through collections-based research.

Reviews of Cherokee archaeology in different areas of southern Appalachia have outlined several specific problems in studying archaeological cultures representing historic Cherokee peoples and their precontact ancestors. Archaeology at Coweeta Creek has much to contribute to dialogues and debates in this literature. What did Cherokee communities look like before nucleated town plans unraveled and were replaced by dispersed settlements characteristic of the late eighteenth century? How did social relationships within and between seventeenth-century towns and villages compare with eighteenth-century social dynamics and geopolitics? What was the nature of trade and exchange in southwestern North Carolina before and after the arrival of Europeans to the Southeast? How did the social composition of Mississippian and historic native households and communities in southwestern North Carolina compare to those in other parts of the Southeast? What kinds of activities took place in and around protohistoric Cherokee dwellings and townhouses, such as those at Coweeta Creek? What impacts would life in native towns such as Coweeta Creek have had on the woodland environments of southern Appalachia? Archaeological materials from Coweeta Creek represent significant data sets relevant to these and many other queries. The following set of Coweeta Creek case studies hopefully will spark further interest in this remarkably rich Cherokee site. These articles are neither a formal site report nor a thorough list of what materials are present in collections from Coweeta Creek. Nevertheless they do contribute to a foundation for the continued study of native lifeways in late prehistoric and protohistoric southwestern North Carolina

The articles in this collection specifically address the Coweeta Creek mound, which represents the ruins of several stages of a public structure. Rodning relates the architectural history of this townhouse to the nature of public life in the ancient town at Coweeta Creek. VanDerwarker and Detwiler compare and contrast the kinds and quantities of plant remains found on floors of the Coweeta Creek townhouse to those found in pits in both mound and village areas. They demonstrate a difference in disposal patterns between pit features in the village and near the townhouse, in addition to considering gendered patterns of food processing in public space. Wilson and Rodning identify the range of ceramic vessels made and used by people at the Coweeta Creek settlement. They offer a functional analysis of pottery assemblages as a baseline for future studies of Qualla phase pottery in the region. Lambert compares bioarchaeological indicators of health and life activity patterns at Coweeta Creek to those at two late prehistoric sites in western North Carolina, Warren Wilson, and Garden Creek.

Hope you enjoyed this long first look at Otto History. These original builders of Otto left much behind. Through the efforts of many, we know they found it to be a truly good place to dwell.

The best source for this article came from Dr. Rodning on this website:

http://www.tulane.edu/~crodning/rodning2011A.pdf

Next Early History Article: The Pottery of the Eastern Cherokee